New professor brings in-depth cancer research to the classroom

Jenifer Leming has spent many years in a lab doing research, but now you’ll find her at the front of the classroom teaching.

Leming is nearing the completion of her first year of teaching at Newman University. She spent the fall semester co-teaching general biology and genetics and in the spring took on a cellular and molecular biology (CMB) course.

Her impressive background in science and her vast knowledge of cancer research is driving her class content in a very pertinent direction.

In the lecture portion of her CMB course, students are studying why the cell behaves the way it does. She hopes this will help students understand how diseases happen in the bigger context.

“Most of these are pre-med students so this is all very relevant to their future careers,” said Leming. “I think I’m doing the right thing by putting very real-world applications that relate to disease into the content of my course.”

Leming has been involved in cancer research since she graduated college. In 2013, she earned a bachelor’s degree in both chemistry and biology from St. Joseph’s College in Rensselaer, Indiana. She spent the summers of 2013 and 2014 working internships in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in medicinal chemistry and biology. While there, she was engaged in developing pharmaceuticals for cancer patients.

She received a doctorate in biological sciences with a focus in cancer biology in August 2017 from the University of Notre Dame. While at Notre Dame, she worked as a cellular biologist in the lab of Reginald Hill, Ph.D., at the Harper Cancer Research Institute. During that time she worked to resolve chemo-resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the third-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the U.S. Leming generated data that led to a clinical trial for a new chemotherapeutic regimen beginning in 2018.

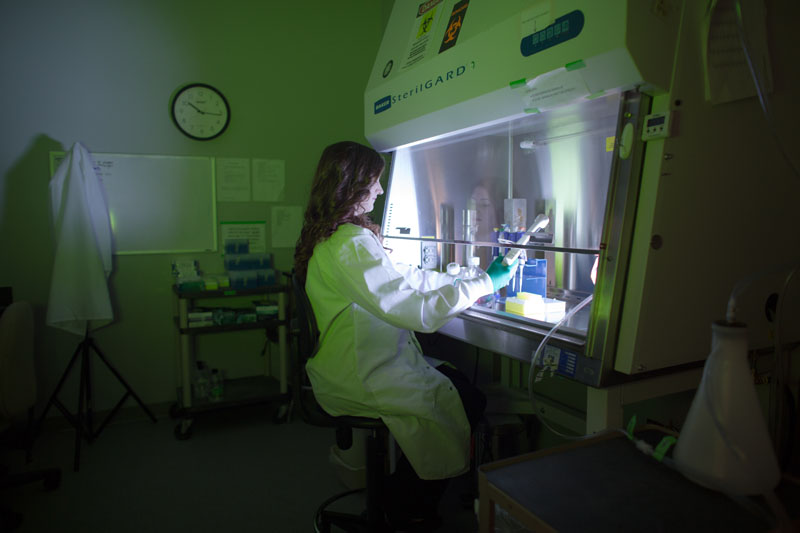

Her work in cancer research has extended to her CMB laboratory students this semester. Leming and her class are working with PDAC cell lines. They are doing experiments and learning techniques that help them characterize the cell lines, focusing on chemo-resistance, protein expression, proliferation and migration of these cells.

Getting students to think more critically about applied science is a priority for Leming.

“The goal for the lab section is to get students in the tissue culture hoods, handling these cells so that they can actually run experiments used every day in cancer research,” Leming explained.

She is taking students a step further by teaching them not only about what particular proteins a cell produces, but also how a protein can affect the behavior of cancer, particularly, why the cancer cells don’t die when exposed to chemotherapy.

As a teacher, “light bulb moments” are what Leming lives for. She said, “When I see that face a student makes when they’ve finally connected concepts, I think ‘I have done my job. I’m done for the day.’”

Leming loves working with the students at Newman as well as the biology faculty. She has been at Catholic universities for the entirety of her higher education career and said, “I love being in a place where science and religion meet. They don’t have to contradict each other, they can complement each other quite nicely.”

During the summer, Leming plans to be in the lab with students doing research on small cell carcinoma of the pancreas (SCCP), a rare and deadly form of pancreatic cancer.

Leming said, “Resources for SCCP research are as rare as the disease. However, I have obtained the only established line of these cells and it is my hope that, this summer, Newman students will be helping me to understand how this cancer behaves and why treatment options may fail.

“We will be investigating potential cellular mechanisms that lead to resistance in this cancer type,” added Leming. “I study stress mechanisms in these cells because when cells get really stressed, like after treatment with a chemotherapy, they start to make proteins that try to tell them to stay alive and hold on a little longer so that chemotherapy can’t kill them. If we can learn the mechanisms that make this cancer difficult to treat, it should improve the chance of developing more effective therapies in the future.

“Essentially, new, targeted therapies help us knock out the survival protein with one drug and then the chemotherapy can come in and knock out the cancer.”